On the Exploration-Exploitation Tradeoff and Identifying Epistemic Actions in POMDPs

TLDR: I study the possibility of identifying epistemic actions in POMDP agents using information value theory.

The exploration-exploitation tradeoff is a core concept in optimal sequential decision-making under uncertainty. The idea is that the decision-making agent does not have complete information about the environment, on the basis of which decisions have to be made. Thus, there is a need to decide whether to exploit the options at hand based on current knowledge about the environment to maximize some criterion (e.g., expected value or return) or, alternatively, to acquire more knowledge about the environment via exploration so that better decisions can be made later. There are two types of uncertainties:

- Aleatoric uncertainty captures the external, irreducible uncertainty, for example due to inherent system stochasticity.

- Epistemic uncertainty captures the internal, reducible uncertainty, often due to partial or incomplete information.

Accounting for aleatoric uncertainty means the agent needs to be conservative, because a decision can lead to both high and low value states and it is not up to the agent’s control. On the other hand, accounting for epistemic uncertainty means the agent will actively seek out situations where additional information can be gained, and these situations may not look immediately favorable from an outsider’s perspective. It is this latter aspect that forms the basis of the exploration-exploitation tradeoff, and it is also a fundamental attribute of human behavior.

Given the fundamental nature of the tradeoff, it begs the question of whether we can distinguish an explorative decision from an exploitative decision when we observe an agent acting in an environment? Being able to answer this question potentially gives us tremendous power, because it is the entry point to switching an agent from the explore mode into the exploit mode. Remember the exploit mode is where most value will be accumulated, while the explore mode is just leading and building up to that. However, this mode-switching mechanism can only be effective and generate substantial impact if there is a clear division, or an either-or relationship, between exploration and exploitation. This requires us to develop a better understanding of the problem of sequential decision-making under uncertainty.

Below, I cast sequential decision-making under uncertainty within the Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) framework and study two properties in detail: observability and the expected value of perfect information. Observability speaks to the hardness of the problem, namely how long one needs to explore and resolve uncertainty before one can start exploiting. However, exploration and exploitation are not always in opposition and they do not necessarily have to be performed in two stages. In fact, as I show using two toy environments, a decision can carry both explorative and exploitative values. This seems to be a huge setback to our agenda of drawing a clear line between the two.

To address this ambiguity, I look to an old concept called the expected value of perfect information, which quantifies how much one is willing to pay for the uncertainty being resolved so that fully informed decisions can be made. This decouples exploration and exploitation in the analysis and provides us a measure of the epistemic value of an action. Given that in different stages of the sequential decision-making process, the epistemic and pragmatic (treated as the opposite to epistemic in this post) values may be different and they generally do not sum up to the same constant, it’s best that they are understood as two different dimensions rather than opposing directions in the same dimension. This draws an interesting (but apologetically hand-wavy) parallel to the concept of valence and arousal in quantifying emotional values.

|

|---|

| HF stable diffusion 2.1: “surrealist painting of optimal tradeoff of exploration and exploitation in sequential decision making”. |

Two types of POMDPs and the role of observability

The problem of sequential decision-making under uncertainty is very well captured by the mathematical framework of Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDP). Very briefly, in POMDPs, agent action \(a \in \mathcal{A}\) causes the environment state \(s \in \mathcal{S}\) to transition from one time step to the next through a distribution \(P(s_{t+1}\vert s_t, a_t)\). The quality of actions are scored by a reward function \(R(s, a)\) either externally given or intrinsic. The agent cannot directly observe the true environment state but a signal \(o \in \mathcal{O}\) generated from \(P(o\vert s)\). The partial observability is the reason why epistemic behavior is important, but exactly how it is important depends on the structure of the POMDP environment, namely the actual observation and transition distributions.

Intuitively, there are two types of POMDPs which I call noisy perception and unknown context.

- In the noisy perception setting, we receive a corrupted image of the true state for example due to sensor noise. This means that the signals we observe in different states may overlap, making it difficult to discern the true hidden state. Imagine a noisy grid world where the states are the discrete grids. In each grid, we receive a signal generated from an isometric Gaussian distribution. The variance of the Gaussian distributions, i.e., the sensor noise, determines how precisely we can infer the underlying states from observations.

- In the unknown context setting, we can typically perceive the current environment state perfectly, but we are obscured from a context variable, which once known can alter the consequences of a decision significantly (either through the dynamics or reward). Consider the following invisible goal-reaching game, where the agent can see exactly which grid it’s in but cannot know where the goal location is until it steps on it or other signaling landmarks. In contrast to the noisy perception setting, the hidden variable here is static and the agent cannot gain much information about it until key context-distinguishing states are reached (like those red paints on trees while you are hiking).

Despite the appeared difference, these two classes of POMDPs can be understood under a common measure of difficulty: \(m\)-step observability, which quantifies the number of environment steps an agent needs to take in order to discern the hidden environment states through Bayes-optimal inference. Smaller \(m\) means the exploration phase takes less time, thus the POMDP is easier to solve and the paper which proposed the notion of \(m\)-step observability calls this type of POMDP weakly revealing POMDP. The step number \(m\) largely has to do with how different the observation distributions for different states are (which can be measured for example as the rank of the observation matrix in discrete environments). The invisible goal-reaching environment is difficult because all non-signaling states share the same observation, while the noisy grid world environment is much easier because only adjacent states tend to have similar observations.

While observability is clearly a central concept, it does not capture another key attribute of POMDPs: the hidden state may be revealed as the agent is approaching the goal, and the process of discerning unknown states and reaching goals might not be in strict opposition. In the noisy grid world environment, for example, since regardless of which direction the agent moves uncertainty is almost guaranteed to reduce, the agent in some sense can “focus more” on moving in the direction of the goal than on finding states where more uncertainty reduction can be achieved. The agent can take “large strides” when far away from the goal and only be more careful as it gets closer to the goal. The same phenomenon however does not carry over to the invisible goal-reaching environment, where the agent will have to purposefully check on each grid, looking as if they remember which grids they have visited and seek out grids that they know they haven’t. Even less intuitive is a special case of invisible goal-reaching (sometimes called T-maze), where the agent can only discern the true goal position in a signaling grid far away from all possible goals. The agent will have to start by moving away from the goals and towards the signaling grid, and only then will the agent know the correct and start approaching it. This creates a highly entangled and problem and situation-dependent picture of exploration and exploitation, which we will try to resolve in the next section.

Identifying epistemic actions using information value theory

In 1966, Operations Research pioneer Ronald Howard made the observation that Shannon’s information theory has an important defect: consider two equally random processes, despite having the same entropy measures, they may have drastically different economic consequences. In the Information Value Theory paper, Howard proposed that the value of information can be measured as the reward or payoff a decision maker is willing to give away in order to have the uncertainty resolved (by a clairvoyant as he writes). Using a simple one-stage decision-making problem, where the agent tries to optimize the immediate reward \(R(s, a)\) given uncertainty (belief) about the environment state \(b(s)\), Howard defines the expected value of perfect information (EPVI) as:

To bring this definition one step closer to the POMDP problem, this interesting blog post proposed a modification of EVPI where the clairvoyant cannot reveal the true state but an observation from the state. The resulting quantity, which I call expected value of perfect observation (EPVO), is defined as:

where \(P(o) = \sum_{s}P(o\vert s)b(s)\). As a side note, the blog post also proposed a generalized axiom of information value, which should have its cost reduced when more information is gained. Both Shannon information and EVPO satisfy this axiom, but for different cost functions.

In contrast to the above decision-making problems, POMDPs has an additional sequential aspect. To appreciate this, let’s write down the (optimal) value function given a belief and an action:

where \(P(o'\vert b, a) = \sum_{s'}P(o'\vert s')\sum_{s}P(s'\vert s, a)b(s)\) is the posterior predictive distribution over the next observation and \(b'(s') = P(s'\vert o', b, a)\) is the counterfactual next belief had \(o'\) been revealed. Singling out the action here is important because we will be analyzing the epistemic value of actions rather than just beliefs. This function is usually referred to as the “expected value” in the literature because it can be shown that the belief is a sufficient statistic of the interaction history and the combination of the posterior predictive and counterfactual belief update properly capture the transition of beliefs, and thus histories, in the environment.

Intriguingly, the similarity between the second term in the POMDP value function and EV\(\vert\)PO shows that the POMDP value function already takes into account the value of information provided by counterfactual future observations. In order to carry on with the information value analysis, we need to define the counterpart of EV in the POMDP context. This leaves us with two types of choices:

- Assume we were forced to make decisions without observing the outcomes \(o'\) for a single step. Outcomes will be revealed to us afterward. We denote this value with \(Q^{1}(b, a)\) and define it as:

where \(b'(s'\vert b, a) = \sum_{s}P(s'\vert s, a)b(s)\) but \(V(b)\) is the optimal value function computed from above.

- Assume we were forced to make decisions without ever observing the outcomes \(o\). We denote this value with \(Q^{\infty}(b, a)\) and define it as:

More broadly, we can define \(Q^{k}(b, a)\) and \(V^{k}(b)\) which measure the value when we are forced to make decisions without observing the outcomes for \(k \in \{1, ..., \infty\}\) steps. We can then define the expected value of perfect observation for beliefs and actions as:

It should be relatively clear that \(k=\infty\) generally gives a better measure than \(k=1\), since there are environments (such as invisible goal-reaching) where a single observation cannot reveal any information. Thus we only study this case.

Related work and discussions

The idea that an action can carry both pragmatic and epistemic value is well known in the POMDP literature. Strangely, it seems to be taken for granted and rarely discussed at length, let alone studied or analyzed in depth. The most explicit exposition of information-gathering actions I have seen is in Nicholas Roy’s thesis, and more recently in the Berkeley RL lecture (under the disguise of RL with sequence models).

What’s equally surprising is that Howard’s expected value of perfect information rarely made it into the POMDP literature. It was mentioned once in Roy’s thesis but never unpacked formally. This paper is one of the only few cases where I see EPVI in the POMDP context. The authors (in fact Roy and his student) proposed chaining open-loop receding-horizon control (treated as EV, which is computationally cheap by ignoring uncertainty) with closed-loop POMDP planning (treated as EV\(\vert\)PO, which is computationally expensive) when EPVI is low. It is thus an interesting showcase of how efficiency can be gained when one is able to decouple exploration from exploitation.

Another POMDP planning framework which tries to explicitly decouple exploration and exploitation is active inference. Active inference can be seen as defining a reward function on agent beliefs which is the sum of a pragmatic and an epistemic term (see my previous posts on the various ways this function can be defined and its motivation and origin). Thus, given an action sequence, one can easily query its pragmatic and epistemic value separately. However, given the vanilla active inference objective does not take into account counterfactual future beliefs but rather future states, it relies heavily on the environment to work in favor of the agent, namely the epistemic term drives the agent to rapidly resolve all uncertainties and only then switch to the exploitation mode. More recent sophisticated active inference solves this problem by taking into account future beliefs, but ends up facing the same problem: the entanglement of epistemic and pragmatic values.

Being able to identify epistemic actions in the wild is of both scientific merit and practical value. Unfortunately, it seems to have been under-appreciated so far. One of the few rare cases where this has been studied is this old 1994 cognitive science paper on distinguishing epistemic from pragmatic action. In the game of Tetris (also known as Russian cubes), the authors found that players may translate and rotate cubes in a way that seems bizarre from an external observer’s perspective, in the sense that the cubes may be moved away from an obvious opening and then back. The only way to rationalize these moves, as the authors argue, is that they advance the players in their internal information state, despite seemingly disadvantageous in the external physical state. The authors also critiqued the ignorance of agent internal reasoning process in Howard’s EPVI framework, mostly on the disregard of subjective probability and sequential nature of decision-making. The upshot is that, in order to understand and identify epistemic actions, one must have a model of how the observed agent reasons. Sadly, despite harvesting a respectable 2000+ citations on Google Scholar, this paper has been taken merely as a symbol of embodied, situated cognition and stopped there, citing the cube-fidgeting example under the abstract concepts of cognitive offloading, mind extension, and memory resource allocation. Only less than 20 citations have attempted to pursue more formal analysis, for example under the frameworks of multi-arm bandits and POMDP. Imagine if we could reliably identify agent exploration in the wild and compress this process without losing the information the agent ought to gain, how much effort could we have saved?

Lastly, to push the boundary even further, the imperfect orthogonality of pragmatic and epistemic values really speaks to the multidimensional nature of agent behavior (I suspect there are more dimensions). One cannot help thinking about valence and arousal in emotion and the temptation to map these concepts on to each other. The situation dependent nature of epistemic and pragmatic values seems reminiscent of the Theory of Constructed Emotions, where the author argues that emotions are not innate but rather behavioral patterns constructed from our interaction with the world. Carrying this spirit forward, we should expect agent-based, embodied, and enactive ideas to help furnish our understanding of abstract social concepts, ultimately bringing more clarity to humanity.

Experiments

Preview of results

In this section, I study how well expected action value of perfect observation (EQPO) can discern epistemic actions from pragmatic actions. The code to reproduce the experiments can be found here.

I use 3 toy environments:

- Noisy grid world: this is a \(5 \times 5\) grid where the agent’s goal is to travel from lower left to the upper right. The agent can only observe a noisy 2-D continuous signal \([i,j]\) sample from a Gaussian distribution for its grid position. The agent gets a reward of 1 if it reaches the goal position and 0 otherwise. The correct behavior is to just move towards the upper right corner. We test different signal noise levels on agent behavior.

- Invisible goal-reaching: This is a \(4 \times 4\) grid where the agent starts from the lower left and tries to reach one of the 3 possible goal positions in the 3 remaining corners. The agent can only observe whether a goal position is the true goal when it reaches that position. The agent gets a reward of 1 if it reaches the goal position and 0 otherwise (no penalty when stepping on the wrong goal). The correct behavior is to cover each goal position and stop at the true goal position once it’s found.

- T-maze: This is a \(3 \times 3\) grid where the agent starts at the top center, right between the two possible goals. The agent can only observe the true goal position when it reaches the bottom center. The agent gets a reward of 1 if it reaches the goal position, -10 when stepping on the wrong goal, and 0 otherwise. The correct behavior is to move away from the potential goals and towards the bottom center. The agent will then know exactly where the true goal is and move towards it.

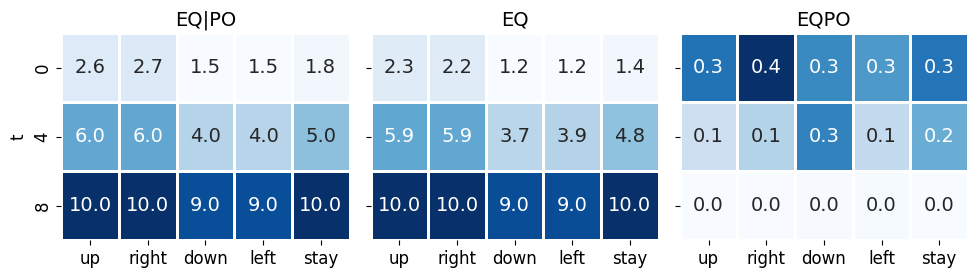

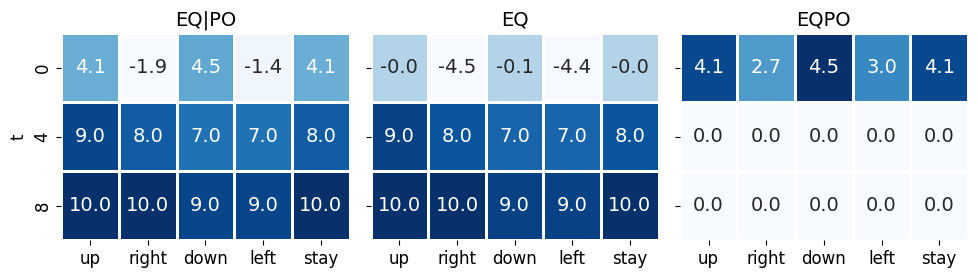

We measure EVPO, EV, EV\(\vert\)PO, EQPO, EQ, EQ\(\vert\)PO in all settings. To reiterate, EQ\(\vert\)PO is just the optimal POMDP action value, EQ corresponds to the expected value of actions without observing future signals, and EQPO is the difference between EQ\(\vert\)PO and EQ. EVPO is just EQPO of the optimal action, and similarly for EV and EV\(\vert\)PO. We refer to EQ as pragmatic value and EQPO as epistemic value.

Generally, EVPO (i.e., EQPO associated with the optimal/chosen action), reduces with agent uncertainty measured by agent belief entropy. In invisible goal-reaching and t-maze, which are less observable environments, there are larger differences between EV and EV\(\vert\)PO.

Our main focus is analyzing EQPO, EQ, EQ\(\vert\)PO to understand the pragmatic and epistemic dimensions of actions. In all environments, actions have very different pragmatic values (EQ). This is reasonable because moving in different directions changes the agent’s proximity to the goal. In the noisy grid world environment, different actions have very little difference in epistemic value (EQPO). However, in invisible goal-reaching and t-maze, actions pointing in the direction of context-revealing states have much larger epistemic value.

We can in fact confidently say that, in the t-maze environment, the first 2 downward actions taken by the agent is purely epistemic, because the first and second best actions in those situations have the same pragmatic values but the best actions has much higher epistemic values.

Methods

I use least-squares value iteration with hand-crafted features of belief vectors and observation sampling to approximate the optimal value functions and policies. Thus, the value function estimates shown below can be a bit noisy but do not obscure the general trend we expect to observe. The t-maze environment requires a different set of features, which I explain in more detail in the code notebook. I use a planning horizon of 10 steps and a discount factor of 1.

Noisy grid world

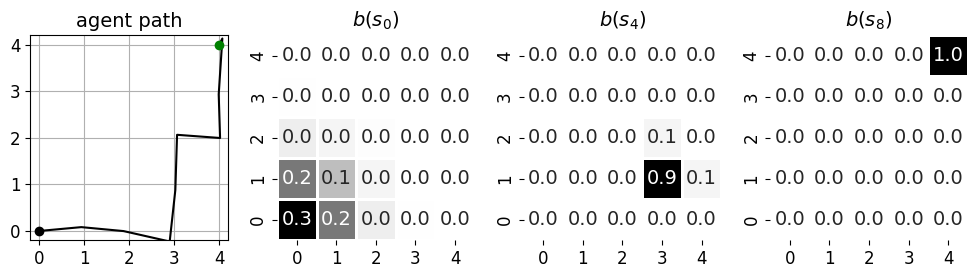

This figure shows an example of the agent trajectory for observation noise level \(\sigma = 1\), starting from the initial position and terminating at the goal (green). The agent’s initial belief about its position is uniformly anywhere except the goal position. After the first observation, the belief \(b(s_0)\) contracts to only adjacent states. The belief \(b(s_4)\) becomes sufficiently certain after the 5th observation.

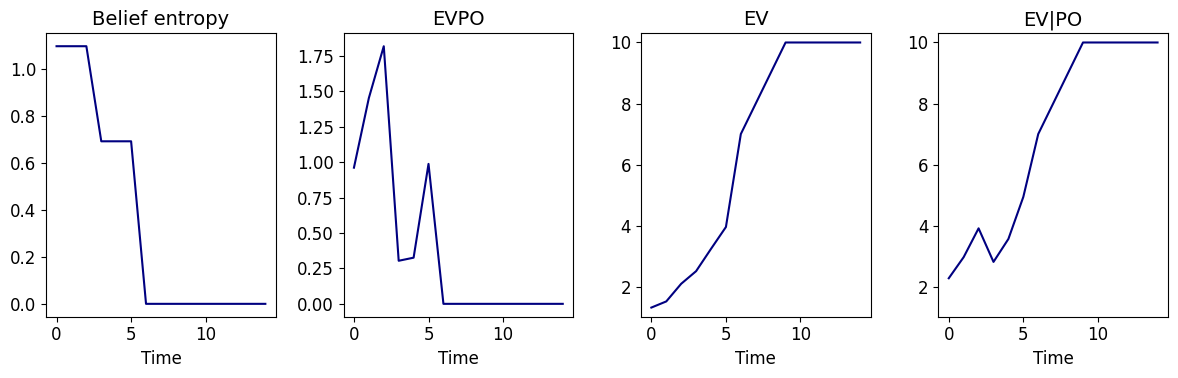

This figure shows that with higher observation noise, the agent remains uncertain for a longer period of time and its belief entropy reduces much slower. The epistemic value (EVPO) decreases roughly at the same speed at which the agent gains certainty. There is little difference between EV\(\vert\)PO and EV even in the beginning of the episode.

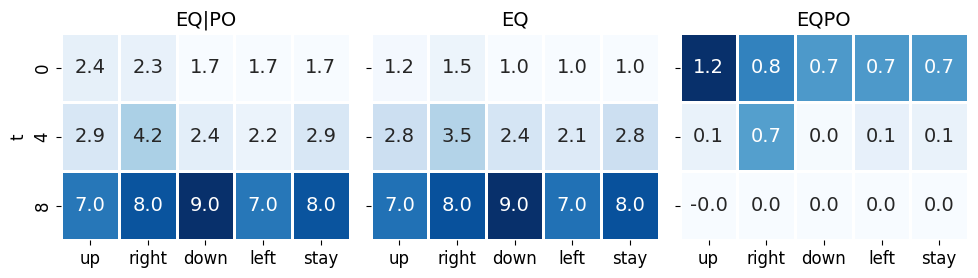

The right panel (EQPO) in this figure shows that there is little difference between the epistemic value of actions at different stages. The actions are mostly driven by pragmatic value.

Invisible goal-reaching

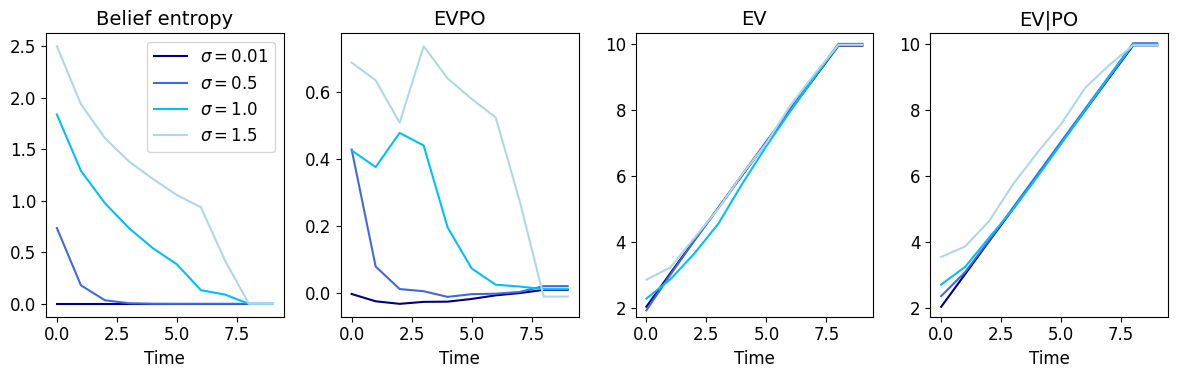

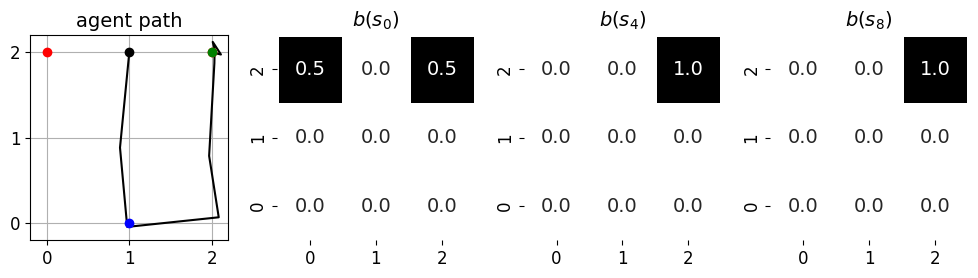

This figure shows an example of agent trajectory. The 3 belief plots on the right show the agent’s beliefs about possible goal positions. The agent starts at the lower left with equal beliefs over all 3 goal positions. It first moves towards the upper left grid and finds out that it is not a goal state. It then adapts its belief \(b(s_4)\) to reflect this and moves towards the second adjacent goal state on the upper right, only to find out that it is also not a goal state. Eventually it reaches the correct goal state at the lower right.

In this figure, we see 2 stages of belief entropy reduction, where within each stage, the agent holds the same level of uncertainty. The two spikes in EVPO and EV\(\vert\)PO parallel the points of belief entropy reduction. It could either be the result of decreasing proximity of potential goals (a form of excitement?) or value function approximation error. We do not investigate further here.

This figure shows that certain actions do have significantly higher epistemic values (EQPO), but in this environment, they coincide with actions that also have high pragmatic values.

T-maze

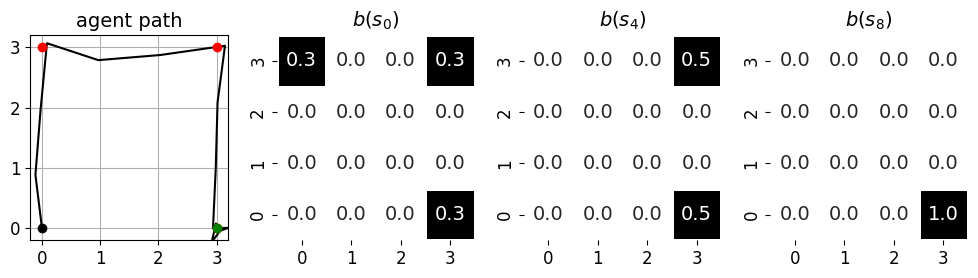

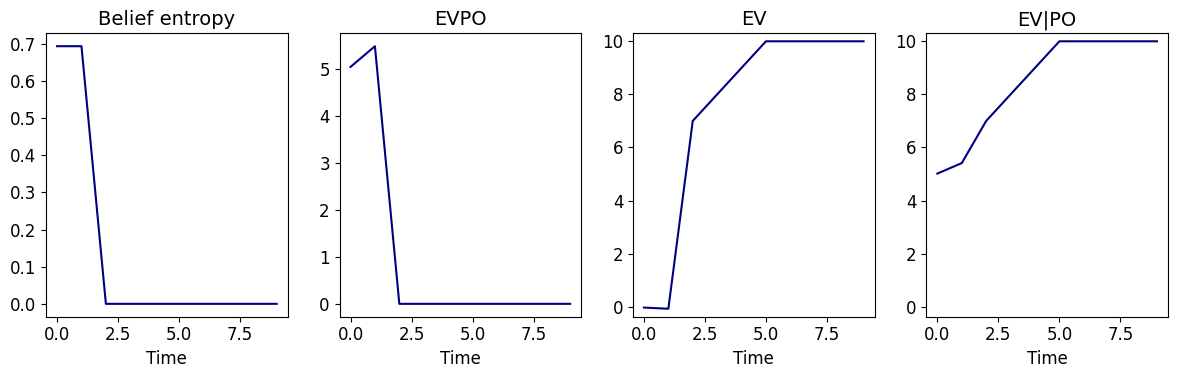

This figure shows an example of agent trajectory, where the agent starts between the two potential goals, but it first moves down towards the context-revealing state and then moves back up after clarifying the true goal position.

This figure shows that the trend of EVPO in this environment almost coincides with belief entropy. Given the initial proximity to goals, initial EV\(\vert\)PO is much higher than EV.

This figure is the main object of interest for the post. It is clear that the sole reason that agent moves down in the first step is to gain larger epistemic value (EQPO), given the top actions in this step have the same pragmatic values.

This example also shows a small caveat in measuring epistemic values at \(k=\infty\). This is because one entangles the epistemic value for a single step with all subsequent optimal epistemic behavior. In this environment, the epistemic value of moving up in the first step is 4.1, almost reaching the epistemic value of the optimal downward action, which has an epistemic value of 4.5. This is because in the initial state (top center), an upward action would cause the agent to remain in the same grid. Since the optimal value function assumes the agent pursues the optimal policy afterwards, it should then move down in the next step and thus only lose a single step of epistemic value.