Resource Rational Adaptive Inference Time Compute

The psychology of optimal compute allocation.

The recent OpenAI O1 release sparked a lot of interests in “inference time compute”, the act of allocating more compute at inference time or test time rather than just training time. Although this is not the first time inference time compute has been demonstrated to be crucial for test time performance, as is done by AlphaGo for board games, Libratus for poker, and many others in reinforcement learning for robotic control and other types of problem solving, demonstrating it on language models and tasks that are so close to our daily lives surely marks a paradigm shift.

In the O1 release blog post and also a recent talk by Noam Brown whose work on poker bots essentially made inference time compute its own subject, the analogy of “if you let the model think more” were made multiple times and was portrayed as the solution to tackling hard reasoning problems (at least that was my impression). This analogy unavoidably makes people fantasize about the connection between O1’s modeling strategy and the popular “system 1 vs system 2” theory of human thinking in psychology.

Naturally, some questions arise that are also interesting to think about from a psychology and cognitive science perspective:

- What makes some problems hard?

- Why inference time compute can improve solutions?

- When and how to optimally allocate compute?

To help with thinking about these questions, I dug up some insights from the RL literature on decision-time planning vs background planning and from the cognitive science literature on resource rational decision making.

Planning in a big world

The prerequisite of planning is having a model of the environment. The model describes how decisions affect outcomes of interest and what outcomes are more desirable than others. The goal of the planner is to search for the decisions that maximally realize desired outcomes in the model.

One way to categorize planning methods is by whether they happen at decision time or in the background (see Alver et al, 2022 for a more detailed and extreme classification). In decision-time planning, the planning operation is performed repeatedly in the face of action selection in response to a specific state encountered. This is akin to running Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) in AlphaGo. In background planning, the planning operation is performed not under the pressure of immediate action selection, but rather to improve a global policy or a value function. This is akin to retraining a large language model every week after having collected enough user interaction data.

There are ways to mix-and-match the two. For example, one of the primary ways to shortcut decision-time planning, in turn making it more efficient, is by replacing longer search depths with a terminal value function, potentially learned from background planning such as in AlphaZero. In this case, the terminal value function becomes another model - a model of “if I start from here and act optimally how much value will I accrue or whether I will win the game”. The mix-and-match can be seen as interpolating between the two approaches, suggesting an inherent tradeoff, essentially between compute and memory (interestingly see Andrew Barto’s talk on RL as smart search and smart caching). However, in the limit of infinite compute or infinite memory, there should not be any difference between the solutions given by the two approaches.

It is clear that the output of the planner in the actual environment can only be as good as the model. While there are some cases where we can ensure the model exactly matches the ground truth environment, e.g., in AlphaGo the model is just the rules of the board games and can be hard coded, more often this is not the case. Traditionally, people have viewed this from a finite-sample or optimization dynamics perspective, but more and more people (e.g., recent papers from Rich Sutton and student Javed, Ben Van Roy and colleagues) nowadays are starting to embrace the “big world” hypothesis which, in contrast to the “small world” hypothesis, holds that the world is so big that even with infinite samples and an ideal optimizer, the model would still be capacity-constrained such that it cannot fit all the information.

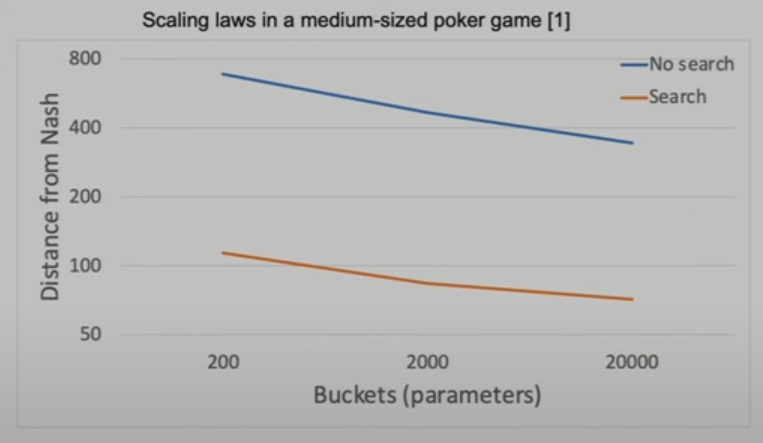

This seems contradictory to the common view that modern models tend to be overparameterized, meaning they are much bigger than what the actual tasks require. But the paper from Javed and Sutton offers two supporting examples. The first example is the language model scaling law, where larger models predictively reduce train and test losses, while these models are already enormous. The second example is AlphaGo, where if the value function had enough capacity and trained on enough data, then there should not be any difference between background planning and decision-time planning, which means MCTS would not be needed. In practice, we do know that the value network in AlphaGo was already pretty large compared to the standard at the time and they did train on lots of data. However, online search still improved performance by 20 percent (see Fig 4 in their Nature paper). One could argue that the model at the time still wasn’t large enough, however the figure below from Noam Brown’s talk on his poker work shows that whatever the model size might be, search reliably and significantly improves performance and the amount of improvement could not be realistically met by scaling up model size. Another argument from Javed and Sutton is that each time we scale the models, the world also becomes more complex as new sensing and behavior modalities are unlocked, so we are trapped in this never-ending chase. In summary, models are bounded.

|

|---|

| Model vs search scaling from Noam Brown’s talk. |

The boundedness of models suggests an interesting, and perhaps individualized or self-referential, notion of problem hardness. Traditionally, the hardness of a problem is characterized by the amount of time or space needed to solve a problem from scratch (e.g., in computational complexity theory). In RL, people have proposed to quantify hardness as the amount of information needed to encode the optimal solution (e.g., mutual information between policy parameters and rewards; see this paper). In contrast, the mix-and-matching planning approach suggests the hardness of a problem should be defined in reference to one’s capability, which can be captured, for example, by the number of additional planning steps needed on top of the base model. This makes sense because what’s hard for one model or person could be easy for another model or person; everyone is built differently.

There are still some interesting nuances in the mix-and-match approach. Even though models are bounded, their sub-optimalities are not equal in all places or for all tasks. For example, for Deepmind’s chess playing model family, we can take it as the value functions are generally bounded, however the transition dynamics models are generally correct or useful (e.g., in MuZero). Language models are still quite prone to “hallucination”, but many of them can post hoc recognize incorrect responses. This means that it is probably fine to use them as transition models or verifiers in language model tree search, despite sometimes being perhaps “too bounded” as action takers.

Resource rational decision making

If we accept models are bounded and thus some problems are harder for the model than others, then how should we optimally allocate compute resources, essentially to harder but also more relevant problems? The suggestion from some psychologists is to lift it to a meta-reasoning problem called resource rational decision making (see Lieder & Griffiths, 2020).

The difference between resource rational decision making and the traditional optimal decision making is that rather than just optimizing problem solutions, the cost of obtaining the solution is also taken into consideration. The joint problem of compute allocation and solution finding is combined into a single meta problem given by the objective below:

Here, \(s\) is the situation faced by the agent, \(m\) is the compute methods the agent has access to, and \(\pi(m)\) is the solutions one can find under the chosen compute method. For example, the compute method could be the hyperparameters of the MCTS algorithms, such as search depth, and zero search depth corresponds to using the cached value function (see an actual implementation of this in the Thinker algorithm). The reward function \(R\) captures the task-solving aspect of the objective, and the cost function \(C\) captures the resource constraint, e.g., more search depths incur higher cost.

|

|---|

| An illustrative cartoon of “planning to plan”. |

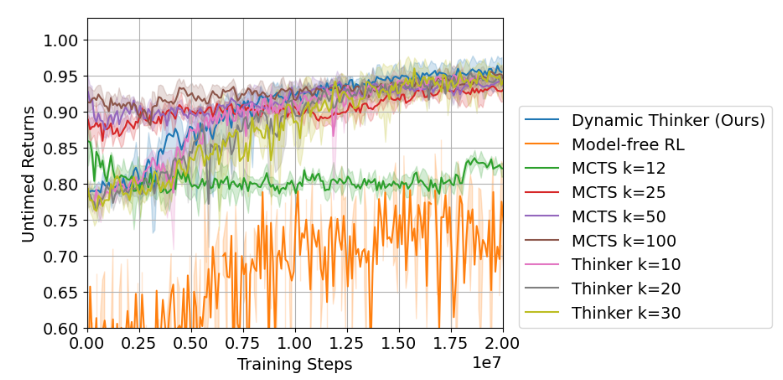

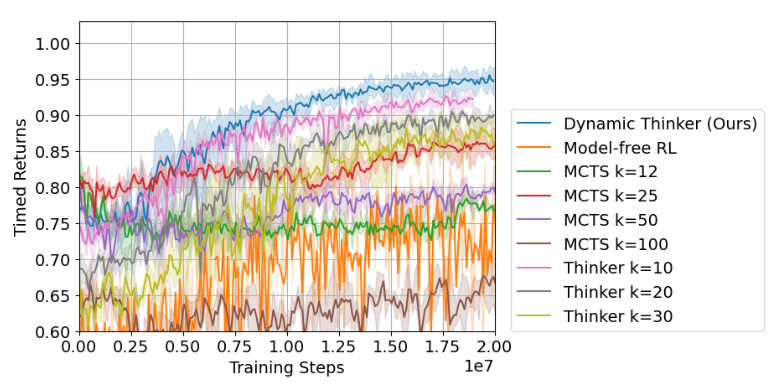

Capturing the problem this ways is very similar to tool-use, where instead of reasoning about what decisions I should make in a situation, the agent asks what compute method I should choose? In other words, the agent is planning to plan (a similar term was used by Ho et al, 2020 in the context of modeling human irrationality). A worked out example is given in a recent algorithm called Dynamic Thinker, which applies this idea to a modified knapsack problem where items need to be packed into a bag sequentially without exceeding the capacity of the bag. Their results in the figures below show that although larger search depths (k) lead to higher task rewards (they call it untimed returns in contrast to timed returns accounting for compute cost), only a small number of search steps are actually needed for the task. Using more steps incur much higher compute costs (timed returns) and thus less of the total resource rational rewards.

|

|---|

|

| MCTS Search depth vs returns with and without compute cost from Dynamic Thinker, 2024. |

Amortized resource rational decision making

Framing the problem at the meta level doesn’t make the task-solving problem any simpler, if only harder because the agent now has even more problems to deal with, on top of decision making problems that are already very hard to solve. How can agents obtain this capability in the first place?

I think the answer is experience and amortization. It does not seem possible for the agent to know on what problems to spend or save compute if it had not encountered similar situations before. Only if the agent has encountered a problem where it searched for a long time and obtained a significantly better solution than started, or searched for a long time and did not yield any improvement, will it know to spend or save compute next time on a similar problem. Such experience could be directly gathered in trial-and-error learning (such as in Dynamic Thinker), indirectly learned from others (e.g., parents and teachers), or inherited from evolution. These experiences are then amortized into the agent such that the choice of compute in new situations becomes implicit and unconscious.

In practice, the more interesting question is how to engineer systems to be resource rational without actually solving the meta-reasoning problem? A few recent studies suggest the way, at least at this stage, is to leverage human prior knowledge to manually construct amortized decisions. In the Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally paper, the authors experimented with a bunch of different training and search compute configurations and found that performance improvement is problem dependent. These experiments then allow them to identify and also choose on what problems to allocate compute at test time. Alternatively, one can train the agent to predict whether more search is useful for the given problem, or even stop a search in the middle. This is done in the Adaptive Inference-Time Compute paper, where the authors trained a language model to predict whether a response generated during best-of-N sampling will remain as the best response after all N responses are generated, i.e., \(P(win\vert query, response)\), if so then one can break the generation loop.

Personally, I still think there are problem structures one could exploit to automatically make resource rational compute choices. For example, if we are able to quantify policy uncertainty such that higher uncertainty means the policy doesn’t know how to solve the problem, and assuming that the uncertainty is due to limited capacity rather than because the optimal solution is actually to randomize, then this is a clear switch to use search. However, this is quite hard to think about because I haven’t seen much if any work trying to disentangle the epistemic vs aleatoric uncertainty in a policy (maybe bootstrapped DQN). Part of the reason is probably that the policy is usually treated as the decision maker rather than a compute method as in the resource rational objective. Reformulating this into a more self-aware representation is likely a promising approach.

Acknowledgements The author would like to thank David Hyland for thoughtful discussions on bounded rationality.

References

- Alver, S., & Precup, D. (2022). Understanding decision-time vs. background planning in model-based reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.08442.

- Javed, K., & Sutton, R. S. The Big World Hypothesis and its Ramifications for Artificial Intelligence. In Finding the Frame: An RLC Workshop for Examining Conceptual Frameworks.

- Kumar, S., Jeon, H. J., Lewandowski, A., & Van Roy, B. (2024). The Need for a Big World Simulator: A Scientific Challenge for Continual Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.02930.

- Lieder, F., & Griffiths, T. L. (2020). Resource-rational analysis: Understanding human cognition as the optimal use of limited computational resources. Behavioral and brain sciences, 43, e1.

- Chung, S., Anokhin, I., & Krueger, D. (2024). Thinker: learning to plan and act. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36.

- Ho, M. K., Abel, D., Cohen, J. D., Littman, M. L., & Griffiths, T. L. (2020, April). The efficiency of human cognition reflects planned information processing. In Proceedings of the 34th AAAI conference on artificial intelligence.

- Wang, K. A., Xia, J., Chung, S., Wang, J., Velez, F. P., Wang, H. J., & Greenwald, A. Time is of the Essence: Why Decision-Time Planning Costs Matter. In Finding the Frame: An RLC Workshop for Examining Conceptual Frameworks.

- Snell, C., Lee, J., Xu, K., & Kumar, A. (2024). Scaling llm test-time compute optimally can be more effective than scaling model parameters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.03314.

- Manvi, R., Singh, A., & Ermon, S. (2024). Adaptive Inference-Time Compute: LLMs Can Predict if They Can Do Better, Even Mid-Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02725.