Empowerment: A New Reward-Free Paradigm for Human-AI Collaboration?

Human-AI collaboration is gradually becoming a mainstream topic, as AI assistants have become prevalent and have started permeating traditional softwares like text and spreadsheet editors. In this setting, humans and AIs co-exist in a shared environment where both of their actions have impact on the environment. From the designer’s perspective, the goal of the AI is to take actions to help humans achieve their goals, typically without knowing exactly or a priori what their goals are.

Currently, the dominant paradigm for human-AI collaboration is reward inference. For example, in RLHF, the AI agent infers a reward function from human ratings of model responses and then adapts its responses to optimize the reward. However, the reward inference approach can be prone to inaccurate inference and reward hacking, which leads the model astray from desired behavior. It thus begs the question: What’s the ultimate objective for human-AI collaboration?

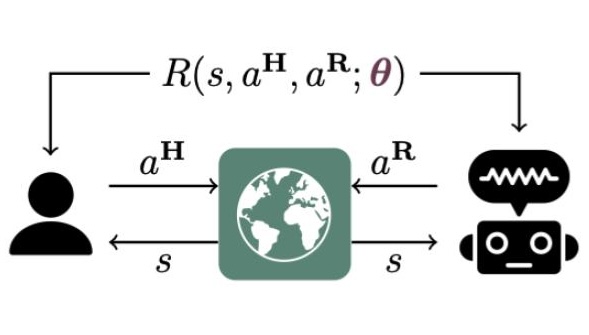

|

|---|

| Illustration of assistance MDP from Laidlaw et al, 2025. |

Recently, there is a line of work exploring an alternative paradigm for human-AI collaboration using a metric called “empowerment”. Empowerment is defined as the mutual information between human actions and subsequent environment states, quantifying how easy it is to predict environment changes given human actions, under the AI’s assistance. We can understand this as how much can the AI’s assistance make the environment more controllable to the human and hopefully their goals more achievable.

Empowerment has been studied as an objective for RL agents in the past. However, this is worth discussing now, because Myers et al, 2024 recently demonstrated an interesting result showing that the empowerment objective lower bounds the reward objective. This means that AI agents optimizing empowerment can effectively assist humans without inferring rewards and suffering from its issues. Too good to be true?

Developing helpful AI via empowerment seems too much of a deviation from the reward inference paradigm, making it hard to understand conceptually.

- How does the empowerment agent model the human?

- Does the empowerment agent make any inference about the human?

- What’s the learning or adaptation dynamics? Will the empowerment agent ask clarifying questions to resolve uncertainty over human goals?

- Is the empowerment agent guaranteed to optimize human reward?

We’ll try to get some clarity on these questions in this post.

The foundation: Cooperative inverse reinforcement learning

Cooperative IRL is usually considered as the foundation for modeling assistive agents. It adopts the inverse RL (IRL) framework by assuming humans will act in a (perhaps noisily) reward rational way. However, it extends IRL to an interactive setting where the human is no longer demonstrating reward-rational behavior in isolation but rather with awareness of the AI agent. This means that the human knows the AI will likely try to infer its reward, the human knows that the AI will act in a way to help achieve higher rewards, and the AI knows the human knows. This setup can induce much more intricate behavior than IRL where the human may exaggerate demonstrations to make its reward easier to infer, the AI may actively query the human for its reward or demonstrations to reduce uncertainty, and the AI may act conservatively without having enough confidence of human rewards (e.g., see this paper on the benefit of cooperative IRL over IRL).

Formally, cooperative IRL models human-AI interaction using the following MDP \((\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{A}^{H}, \mathcal{A}^{R}, R, P, \gamma)\) where \(H\) and \(R\) superscripts stand for human and robot (i.e., the AI, and we will use these two terms interchangeably). The transition dynamics depends on both human and robot actions \(P(s'|s, a^{H}, a^{R})\). The reward function \(R(s, a^{H}, a^{R})\) also depends on both human and robot actions and is only known to the human. The human and the robot have to act simultaneously and independently using policies \(\pi^{H}(a^{H}_{t}|h_{t}), \pi^{R}(a^{R}_{t}|h_{t})\), where \(h_t := (s_{0:t}, a^{H}_{0:t-1}, a^{R}_{0:t-1})\) is the entire interaction history to make the policy class general. The goal of both agents is to cooperatively maximize the expected cumulative reward or return:

where the prior distribution \(P(R)\) represent the set of possible human rewards.

The key result in the cooperative IRL paper is that the optimal policies to this decentralized coordination problem for the human and the robot have the following forms:

This means that both the human and the robot will take actions on the basis on the robot’s belief of human rewards: \(b_{t}(R) := P(R|s_{0:t}, a^{H}_{0:t}, a^{R}_{0:t}) \in \Delta(R)\), which means that the robot will need to form beliefs and make inference of human reward, as we would expect. The beliefs are computed mainly from observed human actions:

Let’s now consider two examples of how the robot will behave under this framework.

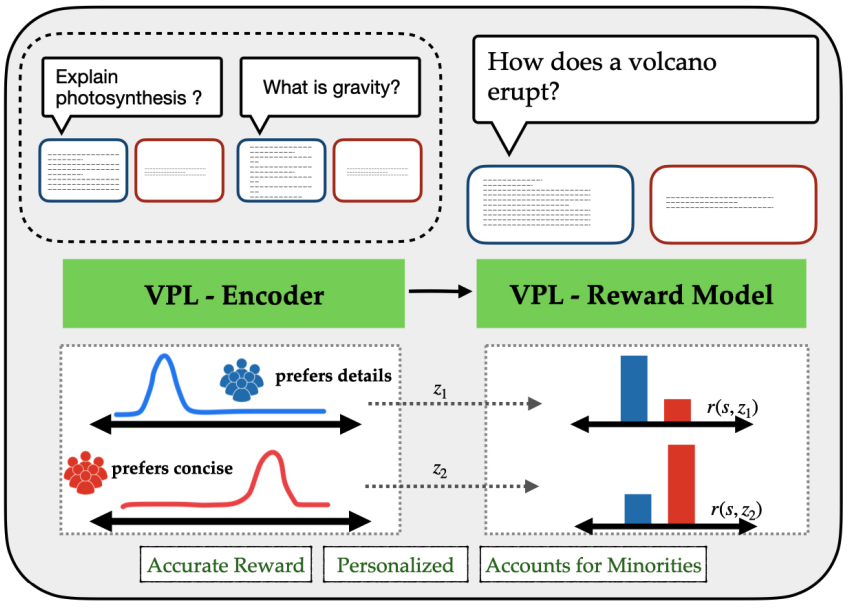

Consider the chat agent setting where the human asks scientific questions and the robot responds with an answer (taken from variational preference learning). The human may prefer either a concise response or a detailed response depending on their internal reward, but this is a priori unknown to the robot. The optimal strategy for the robot in this case, if allowed by other aspects of its reward specification, is to actively query the human for their style preference and generate a response based on that. This uncertainty resolution -> goal seeking strategy is very typical of many problems of this nature. Although nice and simple, this example doesn’t have a strong notion of a shared environment, which is helpful for building intuition of other properties of human-AI collaboration.

|

|---|

| Human goal inference in chat setting from variational preference learning. |

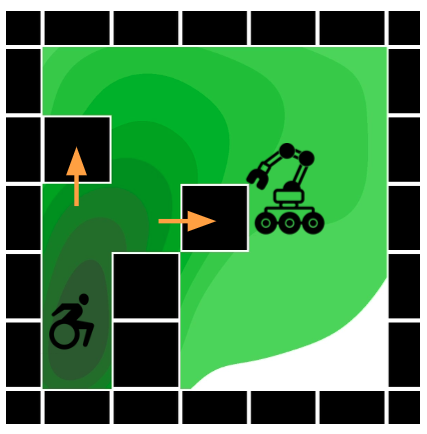

The next example we consider is the gridworld from Myers et al, 2024. Here we have the human starting in the lower left of the grid with a circle of blocks around it. The blocks may or may not be considered a trap depending on where the human wants to go on the grid: if the human wants to go to the upper right, then the blocks are definitely trapping them; but if the human is happy staying at the lower left, then the blocks are there just fine. The robot is a mechanical crane that can move the blocks and open the trap. This defines the shared environment with a more explicit notion of robot actions on human expected outcomes. If the human now wants the robot’s help, for example if it wants to go to the upper right of the grid, it could move up in the trap to gesture its intent. The robot would then help remove the blocks and the rest is straightforward human navigation.

|

|---|

| Assistance gridworld from Myers et al, 2024. |

In summary, it’s relatively easy to reason about the coordination behavior as a result of reward inference. As I am writing this post, Laidlaw et al, 2025 just scaled the reward inference assistance paradigm to Minecraft in an algorithm called AssistanceZero.

Assistance via empowerment

Assistance via empowerment has been studied in a series of papers on a variety of tasks, such as training copilot agents in shared control of a system such as a lunar flight, tuning control interfaces such as eye gaze tracker and keyboard, and training robot teammates in games such as overcooked.

The proposal is to replace the robot reward function with empowerment which is defined as:

where \(h_{t} := (s_{0:t}, a^{H}_{0:t-1}, a^{R}_{0:t-1})\) again is the interaction history. \(s^{+} = s_{t+K}\) is the state \(K\) time steps into the future and the distributions conditioned on human and robot policies \(\pi^{H}, \pi^{R}\) are expected under these policies. For example:

In plain words, empowerment is the mutual information between the random variables of human actions and future states, which can be read as the predictability of future states with and without knowing the human’s current action \(a^{H}_{t}\). This can be seen from the relative entropy representation of mutual information:

which quantifies the reduction in entropy over \(s^{+}\) if \(a^{H}_{t}\) is known.

We can now observe a few differences if we set empowerment as the robot objective, which is defined as:

First, we are no longer being explicit about the human having rewards or not. Second, we do not need to reason explicitly about the coordinated, game-theoretic interaction. The objective is the standard model-free single-agent RL objective.

Needless to say, the authors found merit in this approach. Understandably, the reduction to model-free RL bypasses model-misspecification issues, or at least kicks the barrel down the road.

Empowerment lower bounds reward

The exciting result from Myers et al, 2024 is that even without direct reward inference and optimization, if the human is actually reward rational, the empowerment objective lower bounds human rewards. This is nice because it provides some assurance on the expected behavior of the empowerment agent and the joint outcomes, potentially without falling prey to model-misspecification and reward hacking.

The proof technique is relatively straightforward. First, we need to assume human actions are rational w.r.t. to expected return of human rewards. The authors choose the following Boltzmann rational model:

where the state-only reward \(R\) is assumed to be restricted to the unit simplex, i.e., \(R(s) \in [0, 1]\) and \(\sum_{s}R(s) = 1\). We use \(Q(h_{t}, a^{H}_{t:t+K})\) to denote the open-loop return.

Then the main trick is to establish a series of inequalities to show that the mutual information between future states and human actions lower bounds the mutual information between human reward and human actions, which then lower bounds the expected cumulative rewards:

The first inequality holds because future states are generated downstream of actions and rewards, and the inequality follows from data processing inequality. In plain words, this is saying that the ability to predict human rewards if we know their actions should be no more difficult than predicting future states. This makes sense if the states are harder to achieve than inferring human intentions.

The second inequality is obtained by focusing on the entropies of human actions given human reward using the following bound:

Using the second line plus a lower bound on the Boltzmann distribution entropy for the actions, we get the above result. In plain words, this means that if the environment is constructed in such a way that actually allows the human to achieve the highest unit reward in the long run, then the entropy of human future actions given their reward has the above correspondence with the expected return. There are some tricky details to this which we discuss in the appendix along with other proofs.

This second inequality establishes an important link between mutual information and expected return. Given the fact that expected closed-loop returns are strictly better than open-loop returns, we obtain the final result:

Regardless of whether this is a tight or a vacuous bound, it does say that maximizing empowerment implies maximizing human rewards. This is nice and allegedly the first result of its kind.

What is empowerment optimizing?

The empowerment objective appears very different from the reward inference approach because it does not a priori assume a reward based model of human behavior which allows for training-free online planning and adaptation. However, if we were to think about how the robot were to compute the mutual information without using contrastive estimators used in the paper, then it must have a model of the human. In other words, interacting with the human amortizes the human model into the robot policy.

This became clear as soon as we chose to model human behavior as reward rational in the previous proof. We see that the original state-action mutual information objective basically got swapped by the reward-action mutual information objective in a change of variable. In this sense, the robot policy must learn to make inference of human reward, which makes it equal to the reward inference paradigm on that front.

However, what dictates robot actions is less clear, and there might be a few interpretations. If we interpret mutual information as a measure of information gain, which is highlighted by its KL divergence representation:

Then we can interpret the objective as incentivizing the robot to quickly infer human reward. Yet, this is not useful for actually achieving human reward.

Alternatively, we saw that the main contributor in the proof is the entropy of human actions given human reward. In other words, this term arguably has the strongest effect on robot behavior. If we unpack this term, say for a single time step, we see that it can be expressed as the expected log likelihood of human actions, which under the Boltzmann model, is the expected advantage and is proportional to the expected return:

In this sense, the robot is actually nudging the human to high value states.

References

- Hadfield-Menell, D., Russell, S. J., Abbeel, P., & Dragan, A. (2016). Cooperative inverse reinforcement learning. Advances in neural information processing systems, 29.

- Shah, R., Freire, P., Alex, N., Freedman, R., Krasheninnikov, D., Chan, L., … & Russell, S. (2020). Benefits of assistance over reward learning.

- Selvaggio, M., Cognetti, M., Nikolaidis, S., Ivaldi, S., & Siciliano, B. (2021). Autonomy in physical human-robot interaction: A brief survey. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 6(4), 7989-7996.

- Myers, V., Ellis, E., Levine, S., Eysenbach, B., & Dragan, A. (2024). Learning to assist humans without inferring rewards. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.02623.

- Reddy, S., Levine, S., & Dragan, A. (2022). First contact: Unsupervised human-machine co-adaptation via mutual information maximization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 31542-31556.

- Du, Y., Tiomkin, S., Kiciman, E., Polani, D., Abbeel, P., & Dragan, A. (2020). Ave: Assistance via empowerment. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 4560-4571.

- Poddar, S., Wan, Y., Ivison, H., Gupta, A., & Jaques, N. (2024). Personalizing reinforcement learning from human feedback with variational preference learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.10075.

- Laidlaw, C., Bronstein, E., Guo, T., Feng, D., Berglund, L., Svegliato, J., … & Dragan, A. (2025). AssistanceZero: Scalably Solving Assistance Games. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.07091.

Appendix

In this part, we discuss the lower bound derivation in a bit more depth. Overall, I think that some additional assumptions need to be made in order for the results to hold.

Change of variable in mutual information

The first thing is the mutual information between future states, human actions, and human reward:

The authors say it’s due to the data processing inequality in the following Markov dependency:

It’s not super clear to me whether the dependency between actions and reward is flipped. If so then it’s a bit hard to argue that data processing inequality applies. Nevertheless, it is possible that predicting human reward is easier than predicting future states given human actions. This likely depends on the complexity of the reward set and environment complexity. So the inequality does make sense.

Boltzmann distribution entropy bound

The second inequality restated below:

which links action-reward mutual information and expected return relies on the following property of Boltzmann distribution entropy.

Let a Boltzmann distribution be defined as \(P_{\beta}(i) \propto \exp(\beta f(i))\) with \(k\) output elements where \(f: \{1, ..., k\} \rightarrow [0, 1]\) is a mapping from element \(i\) to the energy value between 0 and 1 and \(\beta > 0\) is the temperature parameter. For the most sharply peaked such distribution, i.e., lowest entropy, the energy values are a one-hot vector, say \(f = [1, ..., 0]\). This distribution is chosen because later we want to upper bound negative entropy, i.e., to find the entropy lower bound on the sharpest distribution. For such a distribution, the normalizing constant is:

The entropy of this distribution is:

The authors claim that:

Intuitively, this bound quantifies how much it deviates from a uniform distribution with entropy \(\log(k)\), which as we would expect depends on the temperature \(\beta\).

To see why, let’s examine both sides of the inequality from small to large \(\beta\). First, we perform second order Taylor expansion around \(\beta = 0\) for each term on the LHS (note: use Symbolab to automatically compute your derivatives):

Plugging into the LHS:

For the inequality to hold, we need:

This holds for all values of \(k\), which means the inequality holds for small \(\beta\).

On the other hand, as \(\beta \rightarrow \infty\), we have for the LHS:

For the RHS:

Again the inequality holds.

Rearranging the entropy bound, we have:

The final thing we need to do is to plug this into mutual information:

The authors claim that:

where \(\hat{a}^{H}_{t:t+K}\) are some uniform random actions. This uses the following property:

and thus:

which leads to the final result.

However, notice that in order to upper bound the mutual information, we need a coefficient \(x \geq 1\) such that:

However, the coefficient chosen by the authors has:

because the values functions are upper bounded by 1. So the upper bound on mutual information is not proper.

Furthermore, the value function upper bound \(Q(h_{t}, a^{H}_{t:t+K}) \leq 1\) also seems flawed. Under the unit simplex reward function, this upper bound only holds if there is a terminal state which has zero reward. Although this is the case for the goal-conditioned setting considered by the authors.

Overall, the result does hold if the human reward describes a goal-conditioned setting with a reward of 1 for reaching the goal, and that the goal is actually reachable under robot assistance.